Book Review: Credulity: A Cultural History of US Mesmerism by Emily Ogden

Like last time, because it’s relevant to this Gymnosophist project, I’m sharing a review I wrote that relates to our lineage here (or one of them)—a piece of the history of spirituality in the U.S., this time from a scholar of English. It is something of a Part Two from the last book, John Modern’s Secularism in Antebellum America.

Three years after Orson Fowler found spirituality in the middle of the top of the head, the mesmerist and phrenologist J. Stanley Grimes located the brain organ for “credenciveness”: religious faith, superstition, and gullibility. Grimes opens not a new chapter of Modern, but Ogden’s Credulity: A Cultural History of Mesmerism, which reads almost as a sequel to Secularism in Antebellum America (I realized after I began reading that Modern is a series editor). Ogden, a scholar of English, continues to expose the fraught Weberian concept of secular disenchantment through her analysis of mesmerists in antebellum America. Phrenologist Grimes counseled that ancient prophets employed an esoteric technique to strengthen the “credensive” organ, a technique they used to control the ignorant masses. Ogden points out that a proper Weberian agent of the disenchanted era would have destroyed these techniques. Instead, Grimes exposed these ancient frauds and then repurposed their practices to new enlightened, rational ends: mesmerism.

Franz Anton Mesmer was a Viennese physician who created a vitalist system of healing based on fluids in the body in the 1770s. It was then thought that a magnetism or force controlled the heavens and inorganic world, and Mesmer applied this theory to all living things. He used magnets, physical gestures, eye contact, and psychic will to affect body fluids and promote healing. Long before Americans engaged with mesmerism, they had learned of its charlatanism. In 1784, ex-pat Parisian Benjamin Franklin was appointed co-chair of an academic committee to investigate Mesmer’s work. The committee, commissioned by the French government, surmised that patients were affected by the treatment because they imagined the healing in their bodies that Mesmer inspired. Their excessive belief healed them, rather than Mesmer’s alleged manipulation of fluid. This finding prefigured later understandings of the placebo effect.

Ogden is not simply interested in credulity. Like John Modern, she is invested in the relationships between secularity and enchantment, specifically between the mesmerist and his credulous patient. She engages Bruno Latour to explore why “the Modern”[1] so furiously needs the credulous to believe and finds that the Paris committee empowered belief in the same way that Mesmer had empowered magnetism. By debunking mesmerism as credulity, enlightened Moderns became more interested and engaged in the practice as something to be incited and managed (33). By the time Mesmerism took off in the U.S. in 1836, Mesmerists explicitly maneuvered their subjects to their own ends. Rather than enchanted primitives (as the narrative went), mesmerists were enlightened, “secular” actors who engaged the credulous in a healing and performative relationship. Ogden is interested in what these disenchanted, secular actors do in response to the “impossible demand that they be empowered and free.” She does not seek to describe secular agency but wishes to understand the effects of “its inevitable failure” as well as the agency of the credulous in relationship to their mesmerists, which intensified after a shift took place in mesmeric practice.

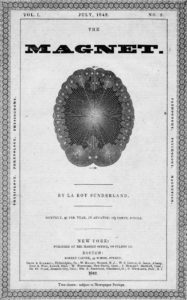

Ogden is not simply interested in credulity. Like John Modern, she is invested in the relationships between secularity and enchantment, specifically between the mesmerist and his credulous patient. She engages Bruno Latour to explore why “the Modern”[1] so furiously needs the credulous to believe and finds that the Paris committee empowered belief in the same way that Mesmer had empowered magnetism. By debunking mesmerism as credulity, enlightened Moderns became more interested and engaged in the practice as something to be incited and managed (33). By the time Mesmerism took off in the U.S. in 1836, Mesmerists explicitly maneuvered their subjects to their own ends. Rather than enchanted primitives (as the narrative went), mesmerists were enlightened, “secular” actors who engaged the credulous in a healing and performative relationship. Ogden is interested in what these disenchanted, secular actors do in response to the “impossible demand that they be empowered and free.” She does not seek to describe secular agency but wishes to understand the effects of “its inevitable failure” as well as the agency of the credulous in relationship to their mesmerists, which intensified after a shift took place in mesmeric practice.

After the Franklin Committee Report and the French Revolution, mesmerism slowed before it regained popularity under Mesmer’s student, the Marquis A. M. J. de Chastenet de Puységur, who would later transform mesmerism into hypnotism. Mesmerists still conducted “magnetic passes” but instead of convulsions, the treatment now produced “somnambulism,” the trancelike state in which the credulous obeyed suggestions and occasionally developed psychic powers. The rapport between doctor and patient fascinates Ogden and she likens it to that of a sorcerer and enchanted victim. Known throughout history in “primitive” religious practices (recall that Howe frequently reminds readers how “primitive” Americans were in 1815) which used trances to communicate with their gods, de Puységur had found the true, secular, scientific reason for the trance: the manipulation of animal-magnetic fluid. But unlike the Franklin Commission debunkers decades before, he would encourage and exploit mesmerism for enlightened purposes—controlling the unenlightened and credulous.

It was this brave new mesmerism that Charles Poyen, a Guadeloupe-born slaveholder, learned at medical school in Paris. When he returned home to the Caribbean, he saw mesmerism being used to control slaves on plantations. In 1836, fifty years after the Franklin Commission, he moved to the U.S. and slowly introduced the country to mesmerism. After a discouraging start, he lectured in Rhode Island where the physician and mill owner, Niles Manchester, saw him speak. He questioned Poyen about a loom worker, Cynthia Gleason, who had suffered poor sleep and nervous affliction for over a decade while working fourteen-hour days, six days a week. Her malaise made it difficult for her to wake for her morning shift. (Can you imagine?) Poyen was hired to address this. Under his mesmeric suggestion, she was trained to rise and shine as promptly “as a dollar bill.” Enchantment here, Ogden says, was a management strategy (76).

Poyen claimed to have implanted his will into the woman and coordinated her rhythms with the factory schedule. He used this “primitive religion updated for modern use”—the will of the capitalists. Are we surprised that American mesmerism, and with it an American occult tradition, was born of labor control? Gleason soon developed clairvoyant powers in her trance states and began to work with Poyen to diagnose other workers’ illnesses. Ogden uses this relationship between Poyen and Gleason as an example of shifting powers between mesmerist and mesmerized, a Foucauldian take on shifting locations of power. This builds on Modern’s analysis of agency in antebellum secularity. That Gleason was able to snatch moments of agency in her diagnoses of other workers’ ailments while “playing” with her submission to Poyen perhaps took the edge off of earning only enough to survive an 84-hour work week.

Are such unequal and shifting locations of power that Foucault proposed really offered to suggest that Gleason has an agency that affects her life in any substantial way? While it is crucial to acknowledge when and how power shifts and agency transforms, it is a dismal mistake to suggest that the oppressed are truly empowered or “healed” by these token agencies. The postmodernist drive to see behavior and culture as entirely conditioned and networked, as both Modern and Ogden argue, can lead to the dangerous attitude that our beliefs, behaviors, and communities are conditioned to the point that our actions are irrelevant and that our world exists post-fact. It also has the soothing effect of letting us off the hook for the State of Things.

Neither scholar is a historian, and these books are far denser and more theoretical than is typical for the history scholarship. Even so, both books provide a rich and fascinating analysis of the emergence and dependence of the secular in an enchanted and Protestant America.

[1] “Latour defines his “Moderns” as those who are “freeing themselves from attachments to the past in order to advance toward FREEDOM.” Ogden, Credulity, 18.

Emily Ogden. Credulity: A Cultural History of US Mesmerism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018.

CATEGORIES: Mesmerism, Hypnotism, Religious Studies, Antebellum U.S. History, 19th-Century Social Change, Spirituality, Literary Theory

PLACE: United States

TIME PERIOD: 1784–1890

Was this useful? Keep us going with a quick tip. Thank you! And buy stuff that you need from the links. Some of them send us kickbacks at no cost to you, but a wee cost to the empire. Thank you! ♥