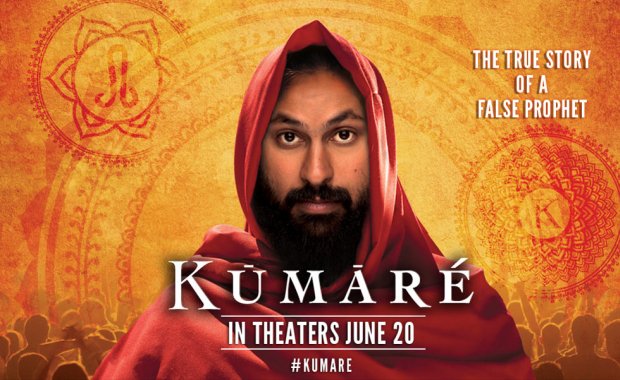

the thing about gurus: a kumaré review

Gurus have always been problem for me, perhaps my biggest in the yoga and meditation worlds. Though perhaps it’s the strange and often appropriated spirituality that bothers me, and gurus are an offshoot of that. The reason I’ve left most sanghas (communities) is because there comes a point that if you aren’t into the guru, you just aren’t going to be accepted or go further. It’s kind of sad.

I teach at a university rather than a studio because most studios require their teachers to drink the kool aid, so to speak. Even studios and meditation centers without gurus tend to have very strong head-teacher personalities and a doctrine to which their teachers must subscribe. Take just a few classes somewhere and you get the idea. If you don’t, take their teacher training. Corporate studios are usually an exception, but they’re corporate. It’s a shame, because a community of like minded yogis or meditators is an amazing thing.

Why are gurus a problem? Because they pretend to have something you don’t. This is Vikram Gandhi’s point in the documentary, Kumaré, playing now at IFC. Because their willingness to be deified is problematic. Because more often than not, they abuse their power. Because they often take advantage of their disciples, sexually and otherwise. Because anyone worthy of being your guru won’t let you deify her. Good teachers encourage personal agency rather than usurp it. That’s what yoga and meditation communities need, amazing teachers.

So Vikram Gandhi’s documentary was poignant. He’s a Jersey-born Hindu who was frustrated by religion. So he studied it at Columbia and was frustrated further (sounds familiar). He didn’t like the YogaGuru madness blossoming in America, and didn’t find them to be more authentic in his motherland of India. So he set out to become a fake guru, to prove that gurus have nothing you don’t. You don’t need anyone but yourself. The answers are within.

Okay. I agree. But what I don’t quite follow is why Gandhi so strongly needed to tell others what they do or don’t need. I’m never terribly comfortable with that. That’s what gurus do, right?

Regardless, the results were great. The first impression I had of the film (full disclosure) was from anecdotes of a student of mine who played Kumare’s assistant. It seemed that its initial intent was to ridicule those who will believe and worship anyone, even a complete fraud from Jersey. But if that was the original intent, it didn’t pan out. What clearly happens along the way is that Vikram falls in love with these people. It changes him. Temporarily, anyway.

I discussed the film with two friends, Surya, who saw it, and Orit, who did not. Orit said “He fell in love with the power, you mean.”

Surya was raised by European parents who followed a Hindu guru. She was part of a spiritual sangha until she was 12. She is incredibly cynical about the experience, yet she agreed. “No, he fell in love with the people. He did.”

And that’s what makes the movie. But it also, for me, disproved his point. The followers needed Gandhi and he needed them, though not as a guru but as a teacher. Because of the circumstances of the documentary, Gandhi was more of a really good teacher than a guru, in the western sense of the word. In Sanskrit, guru generally means teacher, but has a spiritual context which tends to add some baggage. Teachers also learn from their students, at least as much as they teach. The guru tradition is more unidirectional. Knowledge is imparted by teacher to student.

Gandhi was being filmed while he played the role of guru, and not simply filmed, but filmed by close friends and creative partners. He had checks on his power, and he knew the plot: he was going to reveal himself, which forced a certain responsibility and humility, especially when he began to care about his disciples. Instead of behaving like a typical guru, with omnipotence and hubris, he behaved himself while he communicated his message. Because of this he was a powerful teacher. And because he cared.

Gandhi was being filmed while he played the role of guru, and not simply filmed, but filmed by close friends and creative partners. He had checks on his power, and he knew the plot: he was going to reveal himself, which forced a certain responsibility and humility, especially when he began to care about his disciples. Instead of behaving like a typical guru, with omnipotence and hubris, he behaved himself while he communicated his message. Because of this he was a powerful teacher. And because he cared.

I’m not sure that Vikram expected the transformation that came about. I’d guess that he was out of prove his point, not be transformed by his role of the master. But transform he did. As many yoga teachers can tell you, the projections of goodness that students can place on you are powerful. So is the joy of simply helping people feel good. When Vikram Gandhi’s disciples loved him and thought he was great, he felt it, and loved them back. And because his friends were around to film him and keep him in line, and he had to reveal himself in the end, it didn’t go to his head. Instead, he became great, helpful, loving, and caring. And as Gandhi says pretty frequently, “Ask my friends. I am not that kind of guy. I think people miss Kumaré (read: prefer him to me).”

When he said this on stage in a Q&A with cast and crew after the screening, there was a resounding, “Yeah!” from his friends.

The film provokes two questions for me. Do people need gurus? Why wasn’t Gandhi’s transformation long lasting? Or, why does he wish he could always be Kumaré, instead of somehow incorporating Kumaré into himself? Why did he return to his cynical, judgmental self after the filming? That for me is a large question. Did he require the constant projection to be (and feel) loving, open and helpful? Or does he just miss feeling needed and useful?

Do people need gurus? These people clearly needed someone to reflect their goodness and inner guidance back to them, just as Gandhi needed people to reflect his. While I prefer teachers, who am I to tell someone not to seek a guru? I have friends whom I respect, amazing and intelligent people, who believe in a guru. The disciples in the film clearly face difficult problems, issues well beyond existential cynicism, and likely lack solid, understanding relationships in their lives, now and as well as in their tender, developing years.

Do people need gurus? These people clearly needed someone to reflect their goodness and inner guidance back to them, just as Gandhi needed people to reflect his. While I prefer teachers, who am I to tell someone not to seek a guru? I have friends whom I respect, amazing and intelligent people, who believe in a guru. The disciples in the film clearly face difficult problems, issues well beyond existential cynicism, and likely lack solid, understanding relationships in their lives, now and as well as in their tender, developing years.

At one point in the movie, Gandhi talks with a woman who’d been sexually abused by a family member. Just after her interview, he states (I believe as the camera shows her walking off), “We are all really the same” in a very we-are-one guru-y kind of way. I suppose it was meant to make us relate to her, to feel with her, but said at that moment, after that interview, I questioned if Gandhi really gets it. If he gets what it’s like to be someone without a comfortable life, without parents waiting with friends and supporters in the restaurant next door to celebrate his most recent success, with problems larger than showing up to his ten-year Columbia University reunion to face his more successful friends. A personal history filled with trauma and lack of support creates a psyche that aches to be seen and to believe in something more grand than the pain thrown one’s way. Does he get that? Or does he really think they can just find their inner truth on their own? Because, clearly, these people needed to be seen. They needed what Gandhi gave them as much as he needed them. No one can just do it on his own.

Who knows? Maybe he does get it. It’s not clear. I guess that is my question for him. How did making the film change his perception of needing a guru and finding truth on one’s own? Especially in light of his post-filming difficulty finding the same joy in himself as he was able to find in Kumaré.

That said, teachers able to help you believe in your own voice are far far better guides than gurus. In Kumaré, Gandhi is almost as good as they get.

“If he gets what it’s like to be someone without a comfortable life, without parents waiting with friends and supporters in the restaurant next door to celebrate his most recent success, with problems larger than showing up to his ten-year Columbia University reunion to face his more successful friends.”

That is a powerful sentence. If I could venture to answer the first question, I do not think one needs a guru/teacher. I think a person can learn about life and about themselves on their own and learn to be very comfortable in their own skin without guidance. Having a teacher helps, but it is by no means a requirement.

Interesting you chose this line because earlier in the day a friend emailed and said, “Very very very good point!” to the same lines (“If he gets what it’s like to be someone without a comfortable life…”). And thank you for commenting rather than trolling and emailing, like most do. Makes the conversation better. 😉

It also touches on our argument about the young kids stealing fruit off the trees, which means it will probably go in circles. You say “a person” but you really only have your own self and experience to go by, and what you assume others’ positions to be by your particular view of the world. And that’s my point about Vikram. I don’t think he’s in the position to say others can just find their way on their own. While I think gurus are kind of scary, on principle and in practice, it’s not my place to state that someone else doesn’t need one. Or a teacher. While I have had a number of great teachers, I’ve never had a special teacher-student relationship, a person who inspired me and guided me (in yoga or anything else). While I definitely would have liked that and benefited from it, and probably sought it for a long time, it seems my life is touched by friends and students instead. They’ve been my teachers and mirrors. I definitely needed them and continue to do so (feel free to read between the lines there, B). I’m not complaining.

While you might argue that proves your point, I’m not sure that it does. We are both particularly stubborn and probably inclined to learn things on our own, the hard way, and maybe even unconsciously sabotage potential relationships with teachers (who are authority figures) so we can do that. I can only speak for myself. I don’t think it’s the best way, or that it means that someone else doesn’t need a teacher or guru. I’m no more comfortable telling others they don’t need something than I am being told what I do and don’t need. (Okay, fine, maybe a little more comfortable). 🙂

WOW!!!!

Well done!

Selected for Best of Yoga Philosophy.

Bob W.

Yoga Demystified

Thanks, Bob. Appreciated!

I just realized this was written before the recent Bikram suits, which I haven’t paid much attention to, but should be in the public consciousness: http://www.vanityfair.com/online/daily/2013/12/bikram-yoga-sexual-harassment-claims