yoga and the true non-self?

What can you feel? I practice yoga because it helps me feel, which is something I’d trained myself to avoid. It’s an internal exploration that is unspeakably beautiful, and precious few teachers convey this. (Do I? Probably not well.) It’s partly because not many are looking for an internal practice, which means that sticking with an internal focus requires gumption, and partly because it takes far more than language to convey. And perhaps it has never been the point of the practice. Feeling in its raw form essentially alerts us to what we need and don’t need so that we can use our reason accordingly. But many of us are so threatened by our feelings that we repress them entirely. Yoga can help us to sense them again.

Instead, the trend is to use yoga to numb and discipline ourselves. The ancient Yoga Sutras, a non-physical, philosophic text which had limited relationship to physical practice until the 16-19th centuries, when they were slowly integrated, is commonly used by teachers to guide practitioners toward the “true self.” As I’ve noted before, there’s much confusion around this. It is not unusual for an “expert” on the Sutras to spend an hour lecturing about the non-self, and then wrap up his hour with, “Well, I hope you can see that this philosophy provides us with the tools we need to be our true selves.”

Huh? Aside from confusion around what in fact a “self” is, traditionally, yoga (in any of its forms) was never about finding the self, but obliterating it, transcending the self to be one with God. Or emptiness. This search for the self via yoga is a distinctly modern endeavor. That we imagine ourselves to be one with the ancients by using the Sutras essentially as a self-help method is bizarre. But if it works for you, excellent. Go with it. The idea that American yoga is a good-for-you-ancient-physical-philosophical practice is a pop-culture norm, propounded by the likes of The New Yorker and The New York Times, and it doesn’t seem to be going anywhere.

Perhaps the most common part of the Sutras expounded upon in American yoga studios are the Yamas, the first of the eight limbs, moral precepts that read much like the Judeo-Christian commandments deeply embedded in Western Culture. We might take a look at the history of the last 2000 years and ask if these precepts have served us. If we find they haven’t, why are we so quick to snatch them from another tradition, particularly when that tradition aims to obliterate the self? Aside from a special few, this is not what we’re after at all.

On the importance of attachments and ego

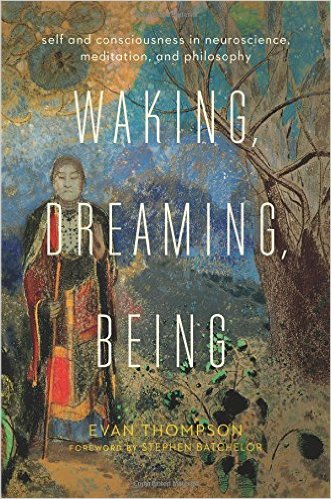

In the last few years, uninspired by the teachings and praxis in our yoga communities, and frustrated by the deep push back against self-awareness that permeates both yoga culture and American culture at large (I’d argue that American therapeutic culture is about creating the appearance of a “happy” self, generally at the expense of difficult or deep self awareness, though I realize this is debatable), I’ve been exploring ideas of the self in European philosophy and psychology. Philosophers the world around (East and West) often hint there is no actual solid, unchanging entity we can call self, and neuroscientists often agree. Evan Thompson, a philosopher known for his work on cognitive science and Buddhism, said in an interview: “In neuroscience, you’ll often come across people who say the self is an illusion created by the brain. My view is that the brain and the body work together in the context of our physical environment to create a sense of self. And it’s misguided to say that just because it’s a construction, it’s an illusion.”

This supports what I’ve come to believe and work with: humans identify as selves. How do we make the best of this? How do we cultivate a healthy, flexible ego that allows us to operate in the world rather than perpetually escape into fantasy?

Let’s say a larger oneness connects us all, if only in that we all share a planet. As developmental psychology posits (psychological ideas are deeply embedded in American culture, so if you’ve grown up here, they impact you whether you endorse a ‘psychological worldview’ or not), as infants, slowly we learn that others are other, separate from us, and with the help of secure attachments to these others, we develop an ego that mitigates our otherness and provides us with a healthy sense of self that helps us relate as separate beings. There is no ego without the other, no me without you. We develop our selves in relationship to the people and culture around us. It is a deluded, neo-liberal fantasy to imagine ourselves to be perfectly independent—but a fantasy that the popular imagination endorses. As humans, we are never fully separate, nor are we never fully merged into oneness (partially, sometimes, but not fully). Many have noted, from Foucault to Ehrenreich, that such a limit experience would blow out our nervous system. This, as I understand it, is where the mad tend to dwell, a little further into the realm of oneness than society deems acceptable. A little blown out.

This is why non-self and non-attachment practices can be slippery for those who didn’t have easy beginnings, with safe, secure attachments. Some estimates suggest that 50% of the American population are not able to create secure attachments. Children who lack safe, healthy attachments often develop very rigid, defensive egos required for self-protection and survival, rather than flexible, healthy egos that allow us to take in and negotiate the vicissitudes of life. Rigid egos are so heavy that we often seek the divine, or spiritual release, or limit experience to escape them, if only momentarily, until the cage comes back down. Neither scenarios are effective in dealing with the day to day, or with putting one’s self out there in all the ways that tend to make humans feel happy and fulfilled: connecting with others, creating, sharing, giving, receiving.

New agers talk about human fluidity and oneness, arguing we need to work back to it. While most of us are far more boundaried and defended than necessary, the urge toward a total fluidity and unboundaried existence is ridiculous. Unless you’ve moved to a cave and renounced world and self alike, you cannot exist without boundaries and the ego and attachments that provide them.

At a meditation retreat awhile back, that guy dominated the discussion, a thirty-something determined to show off what he thought he knew, rather than dialogue. He launched into a story about a relationship he fast became bored with (or afraid of), and when he decided to end it, he told her (and us, as a punch line), “You know, there’s one thing that you can count on, and that’s change!”

Awesome. Buddhist platitudes in the service of avoiding close relationship. Just what we need. I’d wager that this was not change for him at all, but quite likely his habitual, uninformed reaction to intimacy. It’s happened 10, 20, 30 times, and without some serious intervention on his part, will keep on in that vein. And he’s justifying it in terms of spiritual non-attachment? Lordy. This spiritual bypass is sadly common, and these endless platitudes create the fabric of the pseudo-self-awareness of the yoga community.