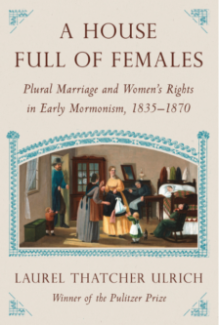

A House Full of Females

Americans are fascinated by the idea of polygamy, in the Orientalism of the harem (which only the wealthy can and could afford to practice), or the former practices of American Mormonism. Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, a Mormon Harvard historian, presents a complicated picture of Mormonism in which some women enjoyed and found agency in polygamy by spiritualizing their labor, and others did not. She claims that Mormon women became political because they wanted the vote, but her evidence supports the likelihood that they wanted the vote to protect their community and faith, rather than rights for women.

REVIEW:

Jeanne Boydston’s Home & Work and Amy Dru Stanley’s From Bondage to Contract: Wage Labor, Marriage and the Market in the Age of Slave Emancipation (1998) offer a lens through which to view the labor dynamic of the Mormon women. Ulrich emphasizes labor with her perennial use of women’s material goods as sources, as well as numerous other examples of women’s unpaid toil throughout the book—including their forced use of Paite women’s labor.

In 2016, Lori Ginzberg, in “Mainstreams and Cutting Edges,” asks why the narratives of people of color and women are still sidelined, rather than having been integrated into the larger historical narrative. It seems unclear to me how these narratives would have been integrated over the last fifty years, when anyone who has been paying attention would note that people of color and women have not been integrated into American society (this was as true in 2015 as now—many just chose not to see it).

American History is written primarily by and for white men (and those who support their narrative, like Ulrich) because white men hold and frame power. Until that changes, I cannot imagine how the writing of history might. That Ulrich’s narratives—full of oppressed people who find redeeming scraps of agency in their femininity or religious choices or ability to adapt to the white man’s incursions on their land, while excluding critical analysis of the power dynamics and economy of that agency—are highly lauded and awarded is ample evidence that “women’s history” has not come very far at all. No one need feel too badly! The oppressed were happy, or at least had ways to try to be, in their own particular way.

(Isn’t it interesting that Foucault critiqued institutional power until he acquired some, and then all of the sudden power had no location (i.e. no one held power). Now power moved?)

Ulrich seems to write in a vacuum. She equates women with femininity as if gender qualities have not been acutely interrogated in the last thirty years. “This is a classic gathering of women performing classic female work [delivering a baby. Is it? Or has this varied through time and space?]” (xix), and most of the labor she mentions in the text involves having and caring for children, cooking, cleaning, making clothes, spinning, “healing,” taking care of crops and animals, note-taking at meetings, and running the Mormon relief organization. While her text is a celebration of women’s work, Ulrich never ties this into the political economy of Mormonism or the larger United States, though it is clear it was extremely significant.

Sutcliffe Maudsley

© Intellectual Reserve, Museum of Church History and Art, Salt Lake City.

Stanley rightly asks where women have gone in the larger conversation about capitalism and political economy in the new narratives of capitalism. Because while we now accept that women are no longer necessarily feminine, we do, I hope, still understand that women hold lesser status and agency in US society, and even more so in the 19th century.

I realize that Ulrich intended to present a complicated picture of Mormonism in which some women enjoyed and found agency in polygamy and others did not. Yet her telling was that of a strange 19th-century cult with members, who may have joined willingly and made great (or convenient?) sacrifices to do so, who may not have had options if they wanted to leave. While the extreme practices of the Mormons were not unusual in American in this time period, Ulrich’s attempts to show the Mormon women’s agency somehow makes the opposite impression. “Although women had no right to ‘Control the Elders and Officers in any manner,’ it was ‘their privilege and duty to warn all’… to make and mend, and wash, and cook for the Saints; and lodge strangers’” (41). Ulrich notes that the female converts “fully embraced” this labor, based on the diary of the apostle and patriarch Woodruff. Such labor was the lot of 19th-century women, and that adding a spiritual element made it bearable, even enjoyable, should not surprise.

I was most fascinated by Joseph Smith’s forcing women to police each other morally by “correcting the morals and strengthening the virtues of the female community (65). It is rare we see evidence of a man encouraging women to police one another, and I found this to be a gem of the book. “But Emma fully embraced her husband’s agenda.” What choice did Emma have? Smith knowingly created a false revelation about polygamy, which Hyrum encouraged (91), and we are to be impressed that Emma was not fooled. Instead, she acquiesced in return for property, bid time while she decided whether the power she enjoyed in the community was worth the humiliation of her husband’s unchecked morals, and with property in hand, left the community when polygamy went public. Ulrich downplays Emma’s desire for another lover and instead wants us to believe that “these men wanted to attract, not command female loyalty” (107). If creating a false revelation about polygamy and demanding that one’s spouse accept it or be excommunicated is Ulrich’s idea of “attracting loyalty,” I fear to wonder at what she might consider force.

© Springville Museum of Art

In all, I was surprised by how rare and mundane the agency assigned Mormon women in this text was. Ulrich seems quite grandmotherly, and her comment that Aristotle’s Masterpiece was a midwife’s manual that men used for illicit pictures of women is simply off— it was an extremely popular sex manual in England, and it was sold as such (Mary Fissell, at Johns Hopkins has done fantastic work on this topic). Laurel Thatcher Ulrich. A House Full of Females: Plural Marriage and Women’s Rights in Early Mormonism, 1835-1870. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2017.

CATEGORIES: Cultural and Social History, Nineteenth-Century U.S. History, Women’s History, Gender History, Mormon History, Religious History, Sex History, Sex roles, Polygamy, Social Marginality, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Mormon Family Diaries, Religious Life.