yoga teachers and teaching philosophies

In oneself lies the whole world and if you know how to look and learn, the door is there and the key is in your hand. Nobody on earth can give you either the key or the door to open, except yourself. ~Jiddu Krishnamurti

A Q&A with students back in 2007

(I’ve taken the old site down.)

Q: How long have you done yoga? Taught yoga? What’s philosophy for teaching a class? —S.L.P.

I took my first yoga class in 1993. Needless to say, I wasn’t hooked. I didn’t even like my first class, an alleged intro class full of pretzel-twisting poses that were way beyond me. I tried & liked other classes, though, and did yoga off and on (more off) until 2002, when I realized it was really quite nice. “Really quite nice” doesn’t merit much time on a busy New Yorker’s schedule. I practiced once every week or two, when time permitted.

During a patch of big stress early in 2003, I realized just how much yoga helped me relax. I began to practice twice a week, and by summer I decided to do a teacher training, not because I wanted to teach (I didn’t. In fact, I didn’t see myself as a yoga teacher at all) but because I wanted to deepen my practice. I trained that fall, and in January, I walked into a job in spite of myself. I’ve been teaching since, and love it more each year. (Short answer: I’ve been teaching a bit over five years.)

My philosophy for teaching a class? I want you to come in, leave your life (good and bad) outside, work hard, meet your body, relax, find your breath, and have fun. How do I encourage this as a teacher? I don’t know. Teaching is extremely intuitive. I practiced daily and have studied with some great teachers. I absorb what I do and don’t like, and try to pass this on to you.

Sometimes I worry that I should do more—go to more teachers’ trainings (I plan to this summer), more retreats, more classes, do more preparation, and so on. But I work full time, I teach about 15 hours a week, and I’m in grad school. Doing more isn’t possible at present. But everything I do brings something to my teaching in a way that living and breathing only hathayoga cannot. I did grad work in South Asian Studies, and now Health and Behavioral Studies/Heath Education. I draw heavily on both in my yoga teaching.

I want people to get into their bodies and be honest with themselves. We neglect and abuse ourselves constantly, and we numb ourselves to life. Yoga can reverse this habit, and it isn’t all relaxation, or love and light, because often we open to the pain we’ve been taught all our lives to avoid. Better to be real and move through the pain (and the joy), than to be rigid and constantly defensive, or bubbly and fake. Or anxious. Or depressed. I’ve found that coming into the body is a remarkable way to do this.

Q: A teacher talked about seeing the good in everyone, even the people you don’t like. That’s not easy. You know, sometimes I don’t want to see the good in someone. Sometimes I just want to hate them. —J.F.S.

While there is merit in seeing the good, it isn’t easy. On one level, I agree with you. I don’t personally find the “be good” lectures in yoga particularly helpful (and there are many). Some may, and that’s great. Use it. But be aware that translated to the western psyche, being good when it isn’t sincere often translates to more anger and repression. If we want anger and repression, why not stick with where we are and forgo all the trouble? Again, I find this true for many, but not everyone.

I, personally, would hate them, if that’s what I felt truly felt. And I’d observe myself doing so, and perhaps, watch how that feels in general, and in my body. While working myself up can feel good and righteous for a bit, when I watch the process of feeling hate towards someone, I find that it doesn’t feel that great at all. It feels hot, leathery, and cramped. If I can feel the anger, watch it pass, and feel my pain and the hurt beneath the angst, I may or may not feel compassion toward the other person, but I sometimes find some for my own pain. And bad habits.

When this happens, I notice all the stories I tell myself about this terrible person and his/her behavior aren’t accurate, or even the point. The point of the stories is to protect me from the pain that I’ve learned to push away and point at someone else.

Part of the brilliance of yoga, when done regularly, is that it opens the heart and clears the mind just enough to want to be good, to not want to hurt others (even if they’ve hurt me), and to be brave enough to face the pain that lies beneath my angry, depressed, or anxiously cartwheeling mind. It’s not about faking like or resisting hate. It’s about being strong enough to observe how my mind works, how my body works, and how I trick myself into more and more pain by trying to avoid the truth of the pain I have. No, it’s not easy, and no, I don’t manage it much of the time.

I didn’t arrive at this by wanting to be good, and even less because someone suggested I should be. I just came to the point, about six years ago, that the behaviors I used to feel good didn’t work anymore, and had never worked very well at all, though they did get me through some hard times. I was making the same mistakes, thinking the same thoughts, having the same conversations over and over and over again. I wanted out, and wanted something else. I knew yoga made me feel good, so I did more of it. That led to meditation, and an intimacy with my mind and how it works.

Wild Geese

by Mary OliverYou do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile the world goes on.

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting —

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

Q: What is the ultimate goal of Western-style yoga from the instructor’s perspective? —A.T.

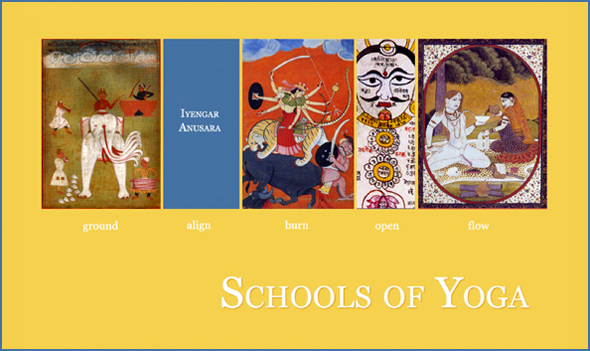

The ultimate goal? Hmm. “Western-style yoga” is extremely diverse and yoga instructors come in many stripes and colors.

From my perspective, the goal of yoga is to connect deeply with myself, to see life more clearly, and allow this connection and clarity to guide my behavior. I ultimately believe that yoga and meditation belong together because they balance one another. Those who only do hatha yoga can unwittingly get locked into physical habits or the exhilaration of the experience. Those who only meditate can unwittingly get stuck in mental habits—or the exhilaration of the experience. But together, they keep a check on the other and balance mind and body.

That said, most of my students don’t meditate. I did yoga about a year before I could sit still long enough to even attempt sitting meditation. For Columbia students, who are already way up in their heads, hatha yoga is very grounding. Sure, meditation would be great for them, but at this point yoga may well be enough.

Q: Given that everyone is different from another, how do yoga instructors evaluate their students’ progress? —A.T.

Most of my students are grad students and with me two years, at the most. They are busy, and most aren’t dedicated to a yoga practice, so even getting to class is an accomplishment. This can make “progress” seem quite slow from where I stand, but they may be getting more benefits than the manic-yogi who shows up each day and rips through the practice out of addiction or habit.

What is progress? I may define progress one way and the student another. My goal of yoga may not agree with a student’s goal, but it doesn’t mean that we are mismatched in the studio.

The idea of a linear progression toward a specific goal doesn’t agree with my perception of yoga as a practice that is at least as cyclical as it is linear. I could evaluate progress along the lines of my last response (“From my perspective, the goal of yoga is to connect deeply with myself, to see life more clearly, and allow this connection and clarity to guide my behavior”). The student who does this may hit a huge crisis and feel as if life is falling apart. From this perspective, that may be the best thing in the world and just what s/he most needs. Ergo, fantastic progress!

If a student wants me to evaluate her/him, or we have a long term relationship, I’d need to know the student’s goals, abilities, and dreams (nothing less!) before I could do so, and even then it would be more about helping the student evaluate her/his practice on her/his own terms.

What about on a simply physical level? I’m not sure there is a simply physical level. Yes, I notice how someone’s down dog is coming along, and can give pointers, but I’m not sure that this is an evaluation of progress. Simply showing up to the mat with a sincere effort to focus on the body and breath is, to me, the biggest accomplishment for any student.