Physical Culture and the Body Beautiful: Purposive Exercise in the Lives of American Women, 1800-1870 (II)

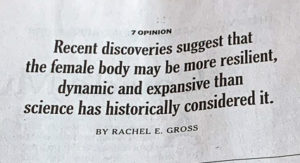

The top headline on a discarded NYT by the window caught my eye as I was reading Todd’s book in a cafe. “Recent discoveries suggest that the female body may be more resilient, dynamic, and expansive than science has historically considered it.” Science has been telling us this, and reneging, for hundreds of years.

Part II of reflections on Jan Todd’s Physical Culture and the Body Beautiful: Purposive Exercise in the Lives of American Women, 1800-1870.

Jan Todd provides a history of women’s 19th-century exercise in this comprehensive, fascinating and fun text. In the 19th-century, women exercised far more vigorously and with more variety than has been appreciated. Rousseau’s influence on women’s education and the “Cult of True (Frail) Womanhood” resulted in the popularity of calisthenics, which has been well documented.

The word “calisthenics” derives from the Greek words for “beautiful” and “strength.” It came about around 1827 to describe a gentle and rhythmic exercise system created in response to women and girls participating in the popular strength-building, vigorous gymnastic exercises of the time. (Gymnastics then meant exercise rather than the elite sport Americans think of today.)

Through archival journals and books, Todd demonstrates that before the 1830s difficult, “purposive” exercises were enjoyed by women in pursuit of what she calls “majestic womanhood,” a Mary Wollstonecraft-inspired vision of strong and competent women. “Purposive exercise physically, intellectually, emotionally influenced women and often empowered them to improve themselves in the world outside their homes.”

Though gentle calisthenics won out for the next few decades, some systems of exercise for women demanded endurance and great strength. Women who practiced them, including Elizabeth Blackwell and Harriet Austin, created a larger and stronger ideal of femininity through the popular ideologies of Lamarckianism, neoclassicism, and phrenology. In a direct challenge to “The Cult of True Womanhood” (see Barbara Welter), they believed that women should be equal to men physically and intellectually. Catherine Beecher, who encouraged exercise within the bounds of women’s domestic place, erroneously receives much credit for women’s physical education. Beecher was not the creator of an exercise system, but an adept marketer.

Purposive exercise was a feature of the 19th-century health reform movement which also included mesmerism, botanical therapy, hydrotherapy, and phrenology, all of which are generally portrayed by recent academics as eccentric and religious quackery. Yet it’s crucial to remember that few scientific advances benefited medicine until much later in the 19th century. Mainstream doctors still practiced “heroic medicine” which involved bleeding, purging, risky surgery and the use of toxic drugs such as mercury, calomel, and arsenic. What was science and what was quackery is not always easy to define, even in hindsight. (Much of what we call pseudoscience now was academically-perpetuated mainstream science back in the day. See: eugenics. I add this to Todd, who comes close to this statement but does not make it.)

Chapter One: Majestic Womanhood vs Baby-Faced Dolls: the Debate Over Women’s Exercise

The Calvinism of the early Northeastern US forbade exercise and dancing, but this proscription had gradually softened by the 19th Century, as strict Protestantism lost adherents to more flexible sects. The rational Christianity of the European Enlightenment influenced many elites, particularly philosophers and physicians (some were both, like John Locke) who noticed that sitting inside reading books all day was injurious to health. Prevention and cure were active recreation.

Influenced by John Locke’s prescriptions for exercise, Rousseau concocted an outdoor life for Emile, the boy in his classic text on education, who learned about the world through physical experience rather than books. The popularity of his 1763 text inspired educators to include various types of physical education in their schools for boys.

Rousseau, whom Todd names “chief prophet of what might be called eugenic womanhood,” did not recommend this life for Sophie, Emile’s ideal wife. Rather, she should be educated to please men, to “be fertile, submissive, non-ambitious and content to stay at home.” This was not simply a reflection of the era, as e.g., Condorcet and Voltaire fared much better, and the Enlightenment period included discussions about what freedom meant for those who were not elite white men.

Mary Wollstonecraft responded to Rousseau in her 1793 classic, A Vindication of the Rights of Women, arguing that women should receive a broad education in rational thought, as well as strengthening exercise. Todd calls this model “Majestic Womanhood.” She who “strengthens her body and exercises her mind will…become the friend, and not the humble dependent of her husband.”* Wollstonecraft was maddened by women who followed fashionable trends, particularly the new elite ideals of female frailty, restrictive clothing, and a sedentary life, which were taught from infancy.

That this upset Wollstonecraft in the 18th Century (1700s) fascinates me. She was frustrated by her peers, the elite women who went along with these boring, unhealthy and restrictive dictates. This is an impossible issue today—many women would rather adopt the status quo, playing pink, weak, and a bit dumb, largely for the power they can eek from it. While men have an obvious stake in keeping women servile, aren’t the rewards of a partner who is not dependent, but instead an equal and engaging companion far higher? Two hundred and thirty years ago, Wollstonecraft hoped that women would have power over themselves (not men), and contrary to the current backlash myth that feminists aren’t hot, Wollstonecraft (as well as many 19th-century American women’s rights advocates) had an unconventional sex life (for the day).

I digress. Todd demonstrates that Wollstonecraft’s ideal of “Majestic Womanhood” found its way to America, where “purposive exercise” was taught by Sarah Pierce in her Litchfield Female Academy in Massachusetts from 1798 to 1833, an earlier start to women’s fitness education than is usually noted.

Continued next time.

*Wollstonecraft as quoted in Todd, Physical Culture, 14.