Hypnosis & Self-Help: A Lineage (or, another book summary/review)

Robert C. Fuller. Mesmerism and the American Cure of Souls. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Robert Fuller writes a history of 19th-century mental healing traditions that connects European Mesmerism to the development of distinctly American religious-psychological traditions such as Christian Science and New Thought.

Fuller positions Mesmer’s healing practice in the Enlightenment rationality of its time. His contemporary and rival, the Swiss priest Johann Gassner, healed through a traditional method, the Cure of Souls—exorcism. Fuller finds the two rituals very like one another, with Mesmer’s based on the science and rationality of the day. As such, it became popular among the “idle elites” in the 1770s.

Mesmer’s new scientific healing ritual replaced the religious tradition for a time. He claimed that there was only one illness and only one healing, a grand claim not unlike those of Catholicism, directed toward human ailments from a sore throat to depression. Because, Fuller argues, Europe had institutions in place that “ordered personal and social life” (or perhaps controlled them), Mesmerism died out once it was debunked, though his pupil Puységur would develop methods of working with the subconscious mind, which developed into hypnotism and exploration of the subconscious and unconscious (see Jean-Martin Charcot and Pierre Janet), ultimately developing into modern psychology and psychiatry.

It was Puységur’s method (still called mesmerism) that entered the United States through the work of his student Charles Poyen, who lectured on mesmerism in the Northeast (see Ogden), putting his subjects in trances and promising remarkable healing. This, as we have learned from Cayleff, Reynolds, Braude, and Modern, was an era of spectacular searching and reform in the young United States (though Fuller does not discuss the social reforms of the era).

Poyen landed in the United States at the time of the second great evangelical revivals, where spiritual searching met communitarian ideas and extensive social reform. Most scholars have more recently agreed that Protestants (who dominated the U.S. scene) reconciled their religion with science, rather than abandoned it. Fuller is the old guard, who argued that this mesmerism allowed Americans to abandon religion for a new psychology—or to hold both in tandem, as a slow shift toward a godless religion of self help gradually emerged by the 20th century. Out of subliminal trance came theories of psychology that met the intellectual and spiritual needs of seeking Americans.

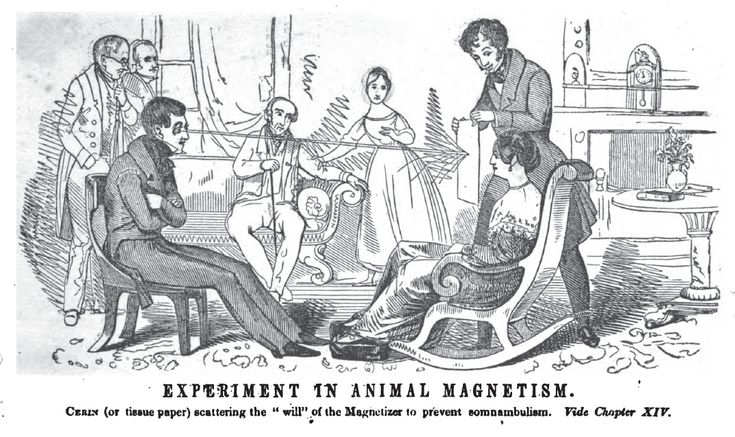

It was, of course, a time of chaotic change (isn’t it always?), and the zeitgeist was heavily individualistic and anti-authoritarian. The evangelical thrust moved away from orthodox doctrines of the Puritans, Presbyterians, and Congregationalist toward more emotive expositions of Christianity. Religious rituals gave way in some circles to the mind rituals of mesmeric trance and healing, and with it, a new psychological approach to understanding health and life. Fuller suggests that the carnival atmosphere of 1840s America led to a mesmerism that “straddled a fine line between religious myth and scientific psychology…. Mesmerism’s explanation of human health and happiness held that personal wholeness was not reducible to mechanistic analysis but rather entered into the finite personality from some transpersonal source” (68). The individual could be in harmony with a divine, vital force if they were willing and able to open themselves to it. This created a space for Americans to eventually move from religious to secular.

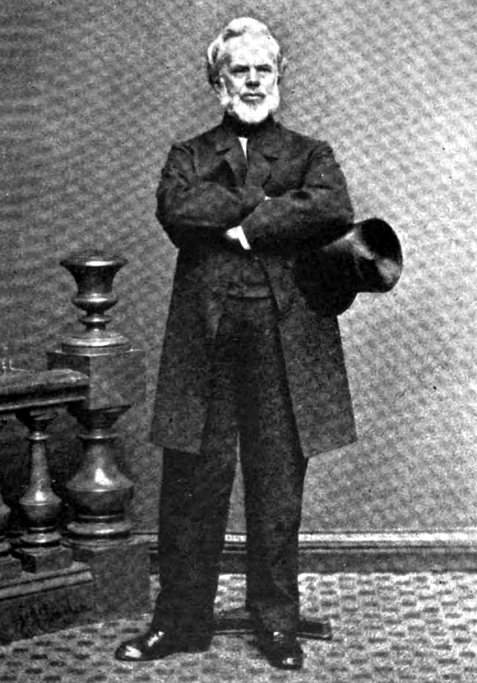

A key figure in that move was Phineas Parkhurst Quimby, who took up mesmerism in the early 1840s. By the 1850s, progressive Christians such as the Swedenborgians, Universalists, and spiritualists found that mesmerism allowed an evidence-based connection with god which offered an individualistic seeking. By the 1860s, Mary Baker Eddy was following Quimby, now an established healer, hypnotist and teacher of the power of mind. Eddy later founded Christian Science.

Fuller argues that Quimby’s teachings were superficial and self-serving. Though Christian Science and New Thought developed from them, which scholars such as Braden and Satter argue had socialist and communitarian leanings early on, Fuller sees only the development of a self-help spirituality that turned into catchy aphorism marketed to self-help seekers who, self-absorbed and narcissistic, could not manage healthy social relationships and community. Instead, they leaned on a positive sound-byte philosophy which allowed them to manage uncertainty and never-ending change in the modern world.

Fuller preaches that without religion, there is no ethical anchor that teaches us to mind our communities as well as ourselves. He connects these 19th century movements to spiritual movements of the 1970s such as EST and transcendental meditation. Though he does point out the introspection of Quimby, he believes it devolved with the mind cure into finding one’s “true self” (150).

Fuller is a religion scholar but offers a history of a 19th-century American slide from religion to secular psychology. New Thought, however, was never entirely secular, and there are far more expansive histories than this, which we’ll cover in the next few weeks.

CATEGORIES: Mesmerism, Hypnosis, Mind Cure, New Thought, 19th-Century U.S. History, Cultural History, Religious Studies, 19th-Century Social Change, Spirituality, Psychology, Psychiatry, Religious Life & Customs

PLACE: United States

TIME PERIOD: 1775-1890 (focus on 1836-1890)

If you’d like to support the site, buy stuff that you need from the links. Some of them send us kickbacks at no cost to you, but a wee cost to the empire.

Thank you! ♥