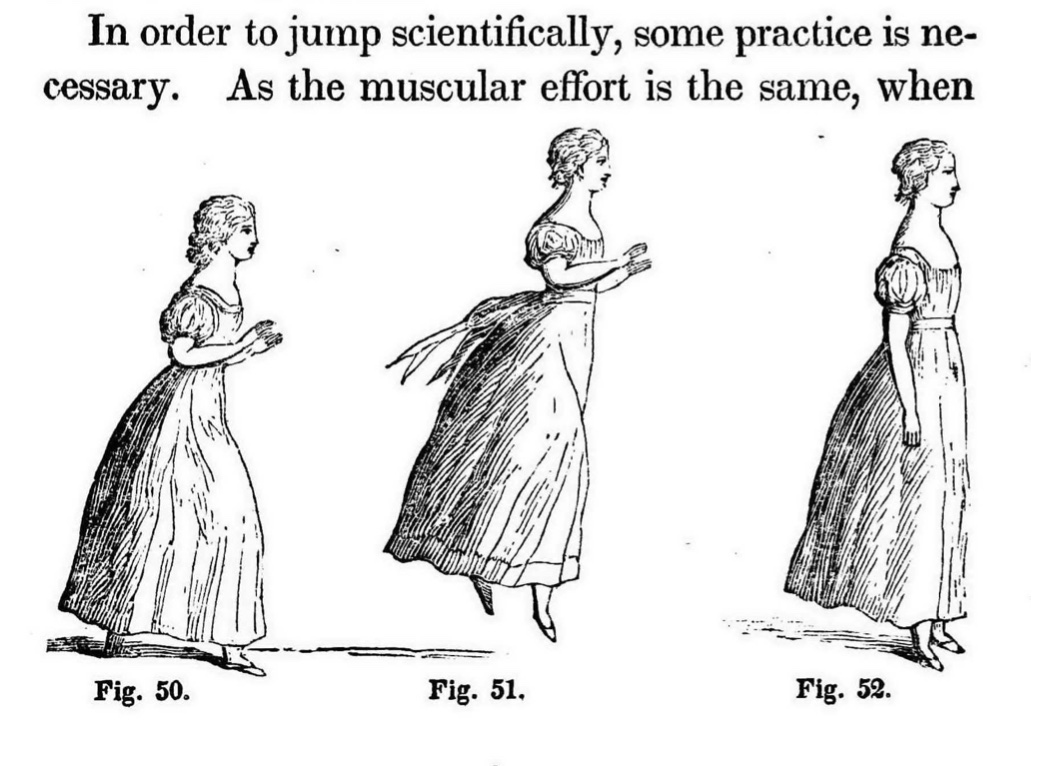

In Order to Jump Scientifically: Todd, Part III

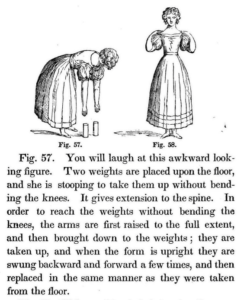

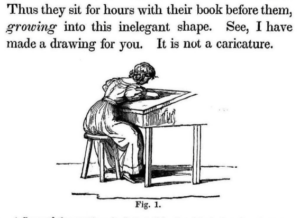

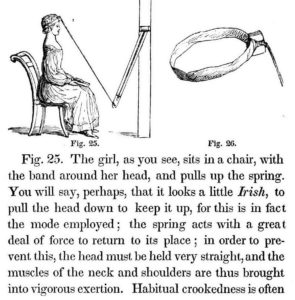

All images are from M.’s A Course of Calisthenics for Young Ladies, in Schools and Families, 1831. I particularly love this illustration. We have used “science-based training” since (at least) 1832. Always so cutting edge, aren’t we?

Further reflections on Jan Todd’s Physical Culture and the Body Beautiful: Purposive Exercise in the Lives of American Women, 1800-1870: Part III.

Chapter Two: “Souls of Fire in Iron Hearts”: The 1820s Gymnastics Revolution for Women

Todd pushes the usual history of women’s exercise back a decade earlier, illustrating a women’s gymnastic movement in the 1820s. The gymnastics movement in Europe influenced the US, starting with Johann Friedrich GutsMuths, a German physical educator at the Schnepfenthal Philanthropic School, which was founded on Rousseauian principles.

Considered the grandfather of physical education, Gutsmuths wrote Gymnastik für die Jugend (1793, Gymnastics for Youth, 1802). His student, Friedrich Jahn, who tied gymnastics to patriotism and masculinity, founded the politically- oriented Turner exercise movement. This people’s movement threatened the prince and the Holy Alliance. Against the crown, Jahn was imprisoned and forbidden to teach, while many of his students fled Germany. Those who came to the United States founded still-active Turner’s Clubs here and had a great impact on physical education in the United States. (I went to a show at LaMaMa last week. The theater is in an old Turner Hall.)

oriented Turner exercise movement. This people’s movement threatened the prince and the Holy Alliance. Against the crown, Jahn was imprisoned and forbidden to teach, while many of his students fled Germany. Those who came to the United States founded still-active Turner’s Clubs here and had a great impact on physical education in the United States. (I went to a show at LaMaMa last week. The theater is in an old Turner Hall.)

As did Pehr Henrik Ling of Sweden, who created a therapeutic gymnastics based on his study of anatomy and physiology, budding and popular sciences of the day. His work influenced American educators Catherine Beecher and Dio Lewis.

Todd argues that Phokion Heinrich Clias had the greatest impact of these early Europeans on women’s exercise, particularly in Britain in the 1820s. Unlike GutsMuths and Ling, he included both boys and girls in his lessons, and published a book on exercise for women. This created a movement of sorts in England in the 1820s, and J.A. Beaujeu noted that most schools in England included gymnastic lessons. He and his wife, Madame Beaujeu, taught a shockingly vigorous gymnastics routine to women in Dublin. Rather than needing lessons in refinement, Beaujeu argued women needed “souls of fire, in iron hearts” (46). His system was designed to promote health and enjoyment.

In 1841, Madame Beaujeu left Dublin for Boston where she opened a well-respected gymnasium under the name of Mrs. Hawley. Horace Mann, Mary Gove, and the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal all praised her school and methods. In the mid-1840s she opened a school near Astor Place in New York. Todd contends that they taught a much more vigorous system to women than has been noted by scholars, and that it benefited women’s health. Information about her lessons spread through American magazines such as the Journal of Health, The American Journal of Education, and the Boston Medical Intelligencer in the 1820s. Exercise was promoted for good health.

Opinion still varied on whether women should perform vigorous, gentle or no exercise, and in the 1830s, gentle exercise took over.

Chapter Three: William Fowle’s Monitorial School for Girls: The First American Gymnastics Experiment

Fowle’s working-class girls’ school was the first that taught exercise in the U.S., predating the commonly-cited Round Hill School for Boys. Fowle encouraged vigorous exercise for women and girls, but by the end of the 1820s, it lost ground to gentle calisthenics (the term was coined at this time to mean gentle exercise for women, as opposed to vigorous gymnastics for men).

Chapter Four: The Literature of Calisthenics

Gustavus Hamilton published his 1827 Elements of Gymnastics for Boys and Calisthenics for Young Ladies in England. Influenced by Rousseau, it seems to be the beginning of the shift to “simple freehand” exercise movement for women which took over for the next few decades.

The first exercise book for women published in the US (most came from Europe) was on calisthenics, and the unknown author called “M.” noted a cultural upper-class anxiety about the effects of indoor, seated education on the mind. “It is astonishing how many perish by what has been called the disease of education” (as quoted in Todd, 105).

Posture correction was a concern, as it has been throughout exercise history.

The author bemoaned that elite women were “misled” to believe that the new model of beauty had become “Of so thin and transparent a hue, you might have seen the moon shine through” (quoted in Todd, 112). Instead, women should not starve themselves in fear of being stout, but look instead to a Greek ideal. “A paid, trained calisthenics teacher” was needed “in every woman’s school.” It is fascinating to see that overly thin women were also an idea in the 1830s. I wonder how their ideal BMI compares to today. Is their thin our thin? How has this changed over time? And how have men’s?

The author’s calisthenics were a compromise between the basic freehand movements of Hamilton and the more vigorous but culturally unacceptable (for women) gymnastics, which would dominate until the 1860s.

Chapter 5: “I Practice Calisthenics Every Day and Like It Quite Well”: Mary Lyon, Mount Holyoke, and American Calisthenics.

Mary Lyon, a chemist and educator, popularized and codified women’s exercise at her school in Massachusetts, Mount Holyoke Female Seminary (which would become the first of the Seven Sisters), where the first U.S. women’s physical education teachers were trained.

Lyon required the young women to do calisthenics, complete an hour of domestic work midday, as a break from studies, run (not walk) up the steps of the school, and spend an hour walking outside before breakfast. In the cold and snowy Massachusetts winters, students were to spend 45 minutes outside, walking only if they could. Lyon’s regimen was in tune with today’s circadian science protocols.

In addition to a shift to more gendered calisthenics and gymnastics, an ideological change in physical education transpired in the 1830s. Physical educators could no longer just teach exercise. Instead, Americans needed to learn both exercise and human physiology—the latter while seated in chairs, rather than while exercising. This became the most popular method of teaching physical education from 1830-1860, disseminated widely by Catherine Beecher.

The popularity of the new science of physiology inspired the belief that simply understanding the body’s anatomy and function could stay healthy without exercise. A woman who learned about her organs would understand how a poor diet, tight corsets, and infrequent elimination could simply be moderate in health matters and stay in good health. Exercise often fell by the wayside, particularly as it was still controversial for women (though teaching her anatomy was as well).

By the early 1860s, when more vigorous exercise came back into fashion, some students found the basic calisthenics silly, but first, Catherine Beecher would popularize—rather than invent—light calisthenics for women.