She looks strong and moves with a will + paul broca, phrenologist + true companionship + 19th C water-cure dating ad

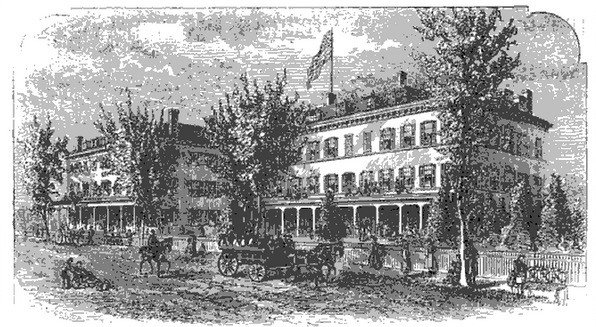

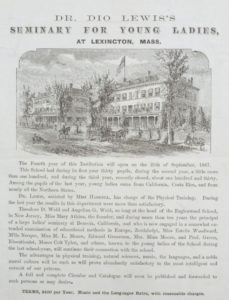

Dr. Dio Lewis’s School for Young Ladies, The American Phrenological Journal and Life Illustrated, Fowler & Wells Company, 1867.

Reflections on Jan Todd’s Physical Culture and the Body Beautiful: Purposive Exercise in the Lives of American Women, 1800-1870: Part V (of V).

Dio Lewis and the New Gymnastics: Birth of a System

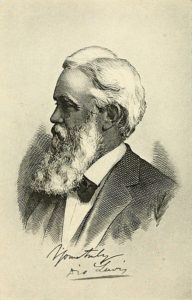

Before Todd’s book, Diocletian (Dio) Lewis had received little historical attention, though his contributions to physical education were well known. He popularized the system of “New Gymnastics,” wrote one of the most popular books of the century on exercise, founded the first teachers’ college for physical education in the US, believed that women should be fully-participating members of society, started a school for their intellectual and physical training, and inspired the Women’s Christian Temperance Union.

Following founding father Benjamin Rush, Lewis prescribed exercise as a treatment for his wife’s consumption, which proved helpful.

In 1856, Lewis traveled to Europe to buy books, visit movement cure organizations, tour gyms, and meet craniologist and phrenologist Paul Broca (yes, that Broca. Our heroes’ embarrassments are usually written out of history). His experiences led him to conclude that Americans were too obsessed with strength and needed to improve speed and flexibility, which Ling’s system provided the Europeans.

The radical Lewis once protected abolitionist Wendell Philips, an indication that his hygiene methods were still connected to the radical reform movements of the 1830s and 1840s. Todd notes that while Dio Lewis was labeled a “crank,” so were Garrison, Phillips, Alcott, H.B. Blackwell, and Lucy Stone” (Nathaniel T. Allen as quoted by Todd, 220). This, to me, serves as a reminder that it wasn’t just the “bad” scientists and politicians, like Paul Broca and Louis Agassiz, who were racist. Racism and eugenics were intellectual beliefs founded in elite science and promulgated by elite institutions. Supporting these ideas was the norm—to challenge them was radical.

In 1860, Lewis opened a public gym in Boston open to women and men. It differed from other gyms in that it offered scheduled exercise classes and two halls with exercise equipment where women and men trained under the eye of drill masters. An annual membership with four classes per week cost $20 (worth $714 in 2022).

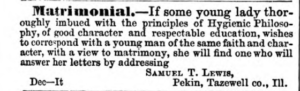

It also housed Lewis’ medical office. There he prescribed his patients “hygienic movement cures.” His wife and several paid female assistants worked one-on-one with each woman patient, as would a present-day personal trainer. In addition to a set of exercises to improve fitness and provide specific remedies, Lewis counseled on massage, early cold water bathing, proper sleep, diet (no caffeine or sugar), and dress.

It also housed Lewis’ medical office. There he prescribed his patients “hygienic movement cures.” His wife and several paid female assistants worked one-on-one with each woman patient, as would a present-day personal trainer. In addition to a set of exercises to improve fitness and provide specific remedies, Lewis counseled on massage, early cold water bathing, proper sleep, diet (no caffeine or sugar), and dress.

Textbooks for Majestic Womanhood: The Literary Legacy of Dio Lewis

“Three of Dio Lewis’s many books bear directly on the question of appropriate women’s exercise: The New Gymnastics for Men, Women and Children, published in 1862, its completely rewritten 10th edition published in 1868; and a lesser-known book entitled Our Girls, published in 1871.

One of my favorite paragraphs of the book, slightly cut but mostly verbatim:

“Lewis understood that body ideology was intimately tied to 19th-century America’s notions of class. ‘If she looks strong and moves with a will, she will be mistaken for a worker, for a servant. If she looks delicate and moves languidly, it will be seen at once that she does not belong to the working class. Don’t you see now how it is? To have a strong and muscular body is to be suspected of work, of service; while a frail, delicate personnel is proof of position of ladyhood. This attitude must stop. It is true that many strong, muscular women are coarse and ignorant but that is because they have given their lives to hard work and have been denied all opportunities to cultivate their minds and manners. To compare such with the petted, pampered daughters of social and intellectual opportunity, and then to treat the strong body of one as the sources of the coarseness and ignorance within, and in the other case, to treat the weak, delicate body as the source of the fine culture, is to reason like an idiot.”

“Whenever women shall rise to true companionship with men as their equals and not their toys, then a small woman will no more be preferred than a small man.” (Lewis in Todd, 255-256). Women should be between 140-160 pounds and big women had a “more dignified character and greater amiability than small women” (Todd, 256).

The Influence of Dio Lewis: “Courage and Strength to Take Up the Battle”

Todd argues that Dio Lewis made a difference in the lives of American women by “raising physical education for women to a new level” and details his all star “Ladies’ School.”

“Reaping the Reward”: The Quest for Health by Lizzie Morley and Her Sisters

A case study of Lizzie Morley and other students of Lewis.

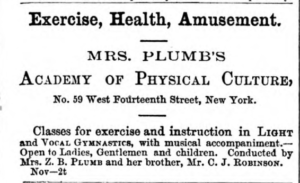

In the 1850s and 1860s, some women opened gyms and schools of physical training. A Mrs. Z. R. Plumb opened the Academy of Physical Culture on W. 14th Street in Manhattan and Mary Hall founded the Brooklyn Ladies Gymnasium on Atlantic Avenue. Both were well attended by prominent New Yorkers.

Grandniece of Catherine Beecher (small circles), Charlotte Perkins Gilman, best known as the patient of Silas Weir Mitchell, grandfather of American neurology and his rest cure, used regular exercise as a means to deal with her gender-enforced economic dependence and confined domestic life (Todd, 290).

After the Civil War, fitness entrepreneurship expanded rapidly. “Rubber chest expanders, dumbbells, Indian Clubs,” other home exercise equipment and various books became popular.

This is the last post on Todd’s history of women’s exercise in the 19th century and, sure, it reads more like notes than the other four. There’s no wind up

summary—it just drops here. See this post if you want a general recap, as I’ve said enough.

I hope you enjoyed! Next up (after a commercial break)? Crusaders for Fitness by James Whorton. Pretty much everything I’ve thought about in the last five years (related to US health), but retro. Also cited in my 1995 undergraduate senior thesis. Or Knowledge in the Time of Cholera by Owen Whooley, which is absolute fire.